Human Waste Disposal in the Backcountry: How to pee and poop in the woods

If a toilet is available, like this outhouse in Southern Alberta, Canada, use it.

(Photo credit: Ben Lawhon)

Most hikers, backpackers, and climbers know that answering the call of nature in the backcountry can present an interesting (sometimes embarrassing) challenge. At the very least, it may cause uncertainty. What are the rules? When and where is it okay to dig? What's this “blue bag” business?

As a growing number of outdoors people head into the backcountry pondering those questions, the impacts on the landscape are growing, too. Some suggested practices are changing as human waste disposal in the great outdoors continues to have serious environmental, health, and aesthetic impacts.

Here, for all of you who've pondered “dig or pack it out?” when rules are unclear, wished for a Port-o-Biff at 12,000 feet, or have worries about using a WAG Bag, are guidelines for taking care of business in an earth-friendly way when you're miles from indoor plumbing.

The Importance of Poop Protocol

According to The Outdoor Foundation's 2009 Outdoor Recreation Participation Report, 7.8 million people backpacked in 2008. The report defined backpacking as spending one night outdoors at least a quarter-mile away from a vehicle. While it's safe to assume that many of those people were just a short stroll away from the loo, let's say that half of them, just once, ventured into the big-time backcountry and were miles from an actual toilet. That's 3.9 million people making, on average and in addition to urine, one number two deposit per day in the wilderness.

In short: that's a lot of poop.

“Human waste and what we do with it can be one of the most significant impacts that faces lands used by the public for recreation,” said Ben Lawhon, education director for the Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics. “It's a disease impact, water quality impact, social and aesthetic impact — and it's something that a lot of people just have a hard time dealing with.”

The aesthetic issue is obvious: no one wants to hike or climb amid exposed human feces or tufts of soiled toilet paper floating merrily on the breeze. Feces contain a cocktail of germs, and no one enjoying the backcountry wants to see it, smell it, come in contact with it, or worse, get sick due to its improper disposal. “Different water-born illnesses are correlated to human use of a given area,” said Jason Martin, operations manager at American Alpine Institute and a Leave No Trace Master Educator. “When that stuff gets in [the water supply], obviously it becomes a problem.”

Take a casual slurp from a clear, gurgling mountain stream and you're inviting the Giardia lamblia parasite to take up residence in your small intestine. A main culprit in water-born illness, the parasite can live for months in chilly ponds or lakes. It gets there through animal or human feces being deposited directly in or too close to water sources. Giardia symptoms, which usually set in a week or two after infection, include diarrhea and abdominal cramps, gas, nausea, sometimes vomiting, and usually a low-grade fever. Cryptosporidiosis, another parasite that causes severe diarrhea, is also a concern, as is Hepatitis A.

According to Mike Smith, a forest planner with the U.S. Forest Service in Colorado's San Isabel National Forest, backcountry waste disposal is a problem many land managers share. High trail use, hikers' improper disposal methods, no mandatory pack-it-out requirements, and a lack of funds to provide education, oversight, and supplies (like WAG Bags, which we'll get to later) make for unappealing encounters on the trail.

Trails in San Isabel's South Colony Lakes Basin, Smith said, see 50 to 100 people every day in the summer season, many of whom spend a night or two, and signs of that heavy use are apparent. “Walk 50 feet from any campsite and you're going to find little white toilet paper muffins scattered around,” Smith said. “There's only so many rocks and trees.”

(Photo credit: Howard Kern)

Places without clear practices may be struggling, but those that have implemented rules have seen success. Eric White, lead climbing ranger on Mt. Shasta in California's Shasta Trinity National Forest said packing out waste became mandatory in 1997. “We average about two and a half tons of human waste that's carried out by the climbers themselves,” he said. “People are getting used to the fact that it has to be dealt with in the alpine environment.”

Lawhon said Leave No Trace's goal is to provide a spectrum of approved options for waste disposal, and it's up to hikers and climbers themselves to determine where on that spectrum they feel comfortable. “We've tried to make it attainable for people to appropriately deal with waste in the backcountry,” he said. “If you say 'gotta pack it out, every time,' you just turn people off. The closer you get to the frontcountry, the more flexible you have to be. It's a continuum, and on one end you've got toilets at the trailhead, and on the other, you've got people packing out their waste.”

Knowing what methods exist, and which method to practice where, can help

assure that wild areas, even well-traveled ones, remain as pristine as

possible.

First, a Word About Number One

Peeing in the backcountry is a relatively simple affair, especially in comparison to human waste disposal. “What we advocate is, pee well away from water sources, trails, and campsites,” said Lawhon. “Based on World Health Organization and CDC [Center for Disease Control] research that has looked at urine, with most healthy people, urine is not a big deal. It's generally very harmless on the environment.”

Always stick to the standard rule of urinating 200 feet from campsites, water sources, and trails; but digging a hole or packing it out isn't necessary. Men have it easy, just aim at an appropriate spot. Avoid peeing on plants that could be defoliated by animals attracted to the salt in urine. Women need to avoid their boots and pants (see Women Only below for tips). Consider diluting the site with extra water to cut down on odor.

Backcountry Bathroom Options for Number Two

A trowel can be essential for the dig-and-bury method.

Once you're out of range of that trailhead toilet, your options for dealing with number two are fairly simple: you can dig a hole and bury your solid waste, or you can pack it out. Those are the main methods Leave No Trace advocates, and those most widely used. Other methods include smearing (yes, you read that right) or tossing. These options, not approved by Leave No Trace, should only be used in rare circumstances, particularly if you're in a very remote area.

Two important things to know before heading out: first, follow the area land manager's guidelines. If the Forest Service says thou shalt pack out waste, then arm thyself with a WAG Bag or other receptacle and follow the rules. “Talking to whatever land manager is in a given area is the most important thing of all. Find out what they feel is most appropriate. Don't assume,” said Martin.

Second, know and follow as many of the four objectives Leave No Trace outlines for backcountry waste disposal:

- Minimize the chance of water pollution.

- Minimize the spread of disease.

- Minimize aesthetic impact.

- Maximize decomposition rate.

Dig and Bury

Digging a cathole and burying feces is the most common backcountry waste disposal method in places that don't have a specific pack-it-out rule. “It's our primary recommendation, if no toilet facilities are provided. We always default to a cathole for most terrestrial environments,” Lawhon said. When the rules for choosing a site and digging a cathole are followed precisely, there are many advantages, outlined in Leave No Trace's principle on proper waste disposal:

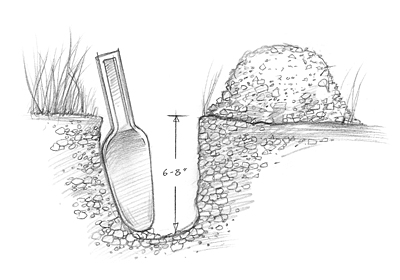

Dig catholes 6-8 inches deep and 200 feet from water, trails, and campsites. (© Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics)

- Catholes are generally easy to dig and easy to disguise afterward.

- They are private, and it's easy to select a remote site other hikers won't encounter.

- They disperse waste, enhancing decomposition.

Your cathole site must be a minimum of 200 feet away (that's about 70 adult steps) from water, trails, and campsites, ideally near thick underbrush, decaying logs or any places other hikers aren't likely to encounter it, and in organic soil to facilitate decomposition. The actual hole must be six to eight inches deep and four to six inches in diameter. A small trowel should be a part of your essential gear for any hiking trip. (Even if you think you'll be near an actual toilet, there's always the chance you'll need to make an urgent stop on the trail.) Know the length of your trowel and use it as your measurement tool when digging.

Once you've taken care of business, the hole must be filled in, covered over (don't touch the waste with your trowel), and disguised with ground material. Be sure to scatter catholes if you're spending more than one night in an area, or if you're camping in a group. “Just because there's nobody there doesn't mean it's not heavily used,” said Martin. “If I'm going to use the bathroom in the woods, I don't want anyone to find it ever again.”

Consider that in shallow catholes, pathogens in feces can remain a health hazard for a year, according to Leave No Trace: A Guide to the New Wilderness Etiquette by Annette McGivney. So, once you've found an appropriate spot, dig the full six to eight inches deep. Avoid digging catholes in areas where the waste is unable to break down, such as arctic, desert, or alpine environments (see Unique Environments below).

Latrines

Catholes and latrines can be dug with a trowel, ice axe, or, in a pinch, a stick. (Photo credit: Ben Lawhon)

Latrines are not commonly used, but you should opt for a designated latrine site “if you're going to be in a large group in one area for an extended period of time, or if you're going to be in a group of people you aren't certain can properly dig catholes,” Lawhon said, such as “kids or others who might not choose the right site or dig correctly.”

Don't think pit toilet; Leave No Trace recommends a latrine be essentially a long cathole. Dig a six-foot trench (length dependent on group size), start at one end, and cover up as deposits are made. Follow the same requirements for site selection and depth as you do a single cathole site: a minimum of 200 feet away from water, trails, and campsites, in organic soil.

Because they have a greater concentration of waste-to-soil, the waste in latrines take longer to decompose than in catholes, up to three years, according to Leave No Trace by McGivney. Therefore, latrines should only be used when necessary.

T.P. Procedures

Aside from your number two deposit, the only other item allowed in your cathole or latrine is white, non-perfumed toilet paper, according to Leave No Trace. But many hikers have differing opinions on whether leaving your toilet paper in the earth is actually appropriate. “The issue is more that you're leaving something that shouldn't be left behind,” said Martin. “There's no reason not to carry it out. It's one small Ziploc, even for a big trip.”

Depending on the habitat and how fast buried waste breaks down, toilet paper can remain long after feces. Bottom line: no one wants to see a blooming bouquet of butt-wipe on the trail. The most astute hiker will pack out their toilet paper, in the interest of truly leaving as little trace of his or her presence as possible. If you must bury your toilet paper, use as small an amount as possible and be sure to dig deep enough.

Many natural materials can be used in place of toilet paper: fallen leaves (identify first), packed snow, even smooth river rocks. Bury the materials in the cathole after using. Baby wipes are effective for personal cleansing, but must be packed out.

Two definite T.P. rules: never bury toilet paper in a desert environment (it's not wet enough to facilitate decomposition), and never burn it (wildfires).

Pack it Out

Many popular, high-use areas like Mount Rainier, Mount Shasta, Denali, and Mount Hood — the list is ever-growing — require you to pack out your waste. And some hikers pack out their poo even when they don't have to, in the interest of trying to make as little impact on the environment as possible.

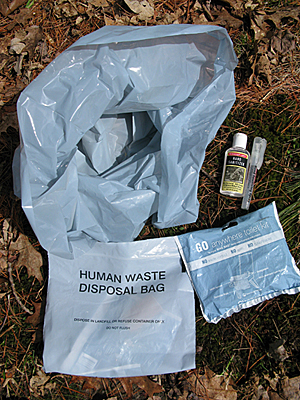

We'll get to the methods in a moment, but first and foremost, having the proper supplies — mainly a reliable, sanitary receptacle and hand sanitizer— is essential. You have several options, from fancy store-bought bags to homemade, rudimentary containers. (Note: even if you plan to dig and bury, it's a good practice to carry pack-it-out supplies anyway, for emergency circumstances we'll address later.)

1. WAG Bag

Wag Bags contain an inner bag and an outer for storage. Remember your hand sanitizer.

WAG (Waste Alleviation and Gelling) Bag has become the overall term for any pack-it-out bag system. It generally involves one bag with which you glove your hand and grab your business and another sturdier, sealable bag in which you deposit and seal the dump. Wag Bags are sometimes called “Blue Bags,” and packing it out referred to as the “blue bag method” because the bags provided to hikers at Mt. Rainier are blue, and Rainier has had a pack-it-out requirement for many years.

Cleanwaste, the company that coined the actual term “WAG Bag,” has renamed their product the GO Anywhere waste kit. It includes a biodegradable waste pickup bag loaded with Poo Powder, a “transport bag,” toilet paper and hand sanitizer. The Poo Powder works by gelling more liquid waste, breaking down solids and controlling odor.

ReStop and Biffy Bags are other manufacturers of waste bag kits, powders, and supplies.

2. Homemade Wag Bag

You easily can create your own Wag Bag using an interior/pickup bag, pre-packed with kitty litter if you wish, which functions similar to Poo Powder, and a larger, sturdy outer bag — think freezer-weight Ziploc. Heavy-duty trash compactor bags work as a Wag Bag trash bag. If bags don't seem sturdy enough, some people use a coffee can as their outer container. Tupperware with a snug-fitting lid that you're certain you no longer need in the kitchen would work, too.

Rangers at Mt. Shasta offer a user-friendly homemade kit to all their hikers, which includes an 11 x 17 sheet of paper with a bull's-eye printed on it for pickup. Just place the bull's-eye on your poo pile, according to White, and you'll have plenty of paper to wrap around it, avoiding all hand contact. Their kit also includes a one-gallon Ziploc bag and a sack with kitty litter. There are disposal receptacles at the trailhead, and hikers can pick up kits there or at area outdoor shops.

Users who make their own Wag Bags should note that homemade versions can't be tossed into landfills, as can EPA-approved commercial ones, like GO Anywhere, Biffy Bags, and ReStop.

“Wagging” Tips

Powders, like Poo Powder above, or kitty litter solidify waste and control odors.

Best practices for using a wag bag come with, well, practice. Generally, when nature calls, you grab your bag kit, toilet paper, bag for used toilet paper, and hand sanitizer and head off to find a secluded area where people are unlikely to encounter your bare bottom. You squat and do your business. You then take your trusty wag kit, slip the inner bag over your hand and grab your poo pile. Be careful not to spill the poo powder or kitty litter inside (so picking up your pile with the top part of the bag is best).

Then, fully enclose the poo and make sure the powder or litter has covered it. In other words, become familiar with touching your warm feces through a layer or two of plastic. It's all part of hiking and climbing! Then, seal that bag inside the thicker, outer bag or stash inside your container of choice. Place your used toilet paper in the bag. Clean your hands with hand sanitizer. Wag complete.

3. Poop Tube

A poop tube is often a climber's preference, but hikers, backpackers, and paddlers can certainly use one, too. You'll need a length of PVC pipe (around 4 inches in diameter), a cap for one end, and a threaded fitting and plug for the other. (For cleaning, it's helpful to be able to remove both ends.) What length you cut is dependent on the length of your trip and, frankly, how much you poop. Six to 10 inches is standard, though 12 to 25 inches is recommended for longer trips. Either secure it to your pack with pack straps, or use duct tape and cord to make a handle and clip it to your pack for easy access. Pack standard coffee filters, place those on the ground, and aim. Or poop into brown paper bags. Then wrap up the business, send it down the tube, and seal it up.

Whether you pack it out in a bag, a tube, or Tupperware, waste should be properly disposed of after reaching the trailhead, often that means into a toilet. Some of the commercially available bags are EPA-approved for landfills, but check rules first.

Pack-Out Musts

Dispose of waste in approved containers or toilets only. (Photo credit: Howard Kern)

Some waste items you always pack out, no matter where you are, what the climate, is or how small an item it is. Those items include tampons, pads, and other feminine hygiene products (see the Women Only section below), and diapers.

Jason Martin, father of two, noted that the Australia-based gDiapers

company offers diapers with inserts that supposedly biodegrade completely

in a compost pile. However, a six or eight-inch cathole does not offer

prime composting conditions. Stick with the Leave No Trace advisement

and pack out all of your baby's dirty diapers.

Smear or Toss

These are little-used methods of disposal for special circumstances. Smearing involves taking solid waste and smearing it thinly on a rock that is off the trail and will receive direct sun, so UV rays cook the pathogens and dry out the dung, and the wind can blow it away.

“It's no longer supported by Leave No Trace, in part because it doesn't seem to be done properly,” said Martin. “The proper way to do the smear technique is to smear it on extremely thinly. A lot of people smear it on like peanut butter.” The thicker the smear, the longer it takes to dry and disappear, meaning there's a great chance of other hikers coming across it. This method should never be used in popular, high-use areas.

The toss method (“We often refer to it as the shit bird,”

said Martin) is used when the environment doesn't allow you to bury —

particularly in high alpine areas, on moraines, or near crevasses. You

make your deposit on a rock and you literally toss it down, or away. The

toss method should only be used in very low-use areas for obvious reasons.

Lawhon said tossing was often employed in coastal areas, with the poop

being tossed out into the ocean on a rock, but Leave No Trace's education

review committee determined there wasn't enough scientific proof that

the waste was adequately decomposing, so they no longer recommend it.

For Women Only

Pee Positions

Finding the proper peeing position and avoiding splatters on your pants or boots requires some trial-and-error practice with the main methods: squat (the often-used, often-disliked-due-to-splattering method), sit, or stand.

Kathleen Meyer, outdoorswoman, former river guide, and author of How to Shit in the Woods: An environmentally sound approach to a lost art, offers up the best step-by-step guide on peeing while sitting and still keeping your pants clean:

- Find a secluded spot with two rocks and/or logs, where you can sit on one and prop your feet up on the other.

- Slide down your pants or shorts (you haven't forgotten your T.P. and hand sanitizer, have you?).

- Set yourself on the edge of one surface.

- Prop your feet on the other surface (you're essentially creating a wilderness potty chair).

- Eliminate.

An old, well-labeled water bottle can serve as a pee bottle (ladies can use a FUD, like the GoGirl, for assistance) or an emergency poop tube.

“It's also possible to master a stand-up peeing technique clothed in a pair of standard loose-fitting shorts — by sliding the crotch material to one side,” Meyer writes. “Practice is the secret, they say.” If you're willing to practice, the key seems to be enough spread in the legs and proper tilt of the pelvis. Good luck; have some sanitary wipes and a fresh pair of drawers handy the first few tries.

Female Urination Devices (FUD's)

Or women can pick up an FUD, a female urination device or director, certain to make all outdoor elimination a cinch. FUD's, like the GoGirl or Freshette, are small funnels. You hold the funnel close, let go, and (in the case of the Freshette) use the hose, well, sort of like a penis. Practice at home, in the shower or over the toilet, before hitting the trail.

Feminine Hygiene Products

On dealing with feminine hygiene products, Leave No Trace's guidelines are simple: Pack out all used tampons and pads. Do not try to bury them; They will not readily decompose and animals may be attracted to them. Do not try to burn them; It would take a very, hot intense fire to burn them completely.

Lawhon said LNT is receiving many inquiries about the DivaCup, a non-absorbent, pliable cup that collects menstrual fluid and has become popular with long-distance hikers. “What we came up with was to cathole that fluid, because it's a biohazard,” Lawhon said. “The same principles apply.”

Pet Waste

In the frontcountry, pack out all pet waste. In the backcountry, treat it the same as human waste: either bury it or pack it out, depending on local guidelines.

"We encourage folks to consider packing out pet waste, even from the backcountry, but realize the practicalities and challenges of this recommendation," said Lawhon. "Therefore, we feel that catholing pet waste is perfectly acceptable."

Standard catholing guidelines should be followed.

Waste Disposal in Unique Environments

Human waste breaks down very slowly, sometimes not at all, in desert, alpine, and arctic environments. Even when buried the bacteria in feces can survive for years, so alternative disposal methods should be followed in these environments.

Above Tree Line

Alpine environments are far more delicate than the land below tree line. Again, Leave No Trace advocates for the pack-it-out method. Lawhon recommends not making camp above tree line. Digging a cathole is the last resort. “If you have to do it, move a big rock and dig under that large rock, rather than plunking your trowel down on delicate vegetation,” he said.

If you need to pee above tree line, urinate on rocks or bare ground, not on plants.

Desert

“We advocate shallower catholes, in the two- to six-inch range,” Lawhon said. Keeping the waste higher in the soil horizon maximizes decomposition. Look for organic soil under trees and avoid cryptobiotic soil crust, which is extremely fragile.

Winter

Above tree line and in winter, it's best to pack it out. Otherwise, you're leaving behind frozen waste for the next visitors.

Leave No Trace outlines three options for solid waste, in order of preference. First, pack it out. This is the preferred option, since poop can remain frozen in winter (which means you won't have to deal with any odor). Second, attempt to find a snow-free area like a tree-hole where you can actually dig. Third, dig a snow cathole.

“The key is, you've got to look at your map and make sure you're not dumping near a creek,” Lawhon said. And keep in mind that if you choose the third option, you're throwing LNT objectives three and four (aesthetics and decomposition) out the window. If you're on solid ice, packing it out is best.

Come spring, no one wants to find your semi-frozen waste on the trail. So, if you do choose the third option, do it off travel ways and away from water sources. Choose a spot with sunshine, make a hole, cover your business, and let the snow melt dilute it. Snow works well as T.P.

As for peeing, cover any spots of yellow snow and pee away from water sources.

River Canyons

In river canyons where you may not be able to get 200 feet away from the water, Leave No Trace advises to urinate directly in the river for dispersal ("dilution is the solution") and to pack out all feces. “Packing out your shit is part of the culture, and I hope that becomes part of the culture in other user groups, too,” Lawhon said. Some paddlers and rafters carry a portable, reusable toilet system that they empty out later, or a poop tube.

In a few areas with low-volume rivers, it is illegal to urinate in the river, so follow the local guidelines. In those cases, it is recommended that liquid waste be dispersed away from camp and well above the high water line.

Tent Bound

For any circumstance under which you're confined to your tent, you're going to need a receptacle, like your homemade poop tube or pack-it-out bag and container, or a water bottle can serve as last resort (here's a use for those retired BPA-leaching bottles; label well). When urinating, aim very carefully, with the bottle's opening as close to your body as possible (ladies, use that nifty feminine funnel to ease the process).

For number two situations, if you have no poop tube, this is your opportunity to use that extra wag bag/pack-it-out kit you've surely remembered to pack. Obviously, since you're in your tent instead of on natural terrain, the method is a little different. You're going to have to slip the plastic bag over your hand and play catch, or use the coffee filter you've brought with your poop tube. No kit? You can use your spare water bottle, hold it close and aim carefully, adding it to your pee, and then dig and bury when the opportunity presents itself. Basically, make your water bottle a makeshift poop tube. An appealing thought? No. Necessary in emergencies? Perhaps.

Finding Your Comfort Level

A toilet in California's Sierra Nevada. (Photo credit: Howard Kern)

In dealing with your waste outdoors, it's important to remember Leave No Trace's overarching advice: find someplace along the continuum, in between trailhead toilets and poop tubes, where you feel comfortable. If you're not willing to pack out your waste, some incredible outdoor spots will be off-limits to you. However, many others are easily within your reach, so long as you dig an appropriate cathole.

Can't stomach the thought of carrying around your dirty T.P.? Well, you can bury it, so long as you understand it might be there a long while, and really didn't belong there in the first place.

Ultimately, respect the proper practices, check with area land managers before your trip, and do your part to keep the wilderness pristine. Meyer, whose book was the first to truly be frank in explaining the necessity of proper backcountry disposal, sums it up well. “Unfortunately, I think we can expect ever-tightening regulations unless, as individuals, we jump up and take the initiative to learn how to live gently alongside Mother Nature.”

Even if it means having to pick up your own poo once in a while.

For more information

Leave No Trace Center for Outdoor Ethics

Leave No Trace: A Guide to the New Wilderness Etiquette by Annette McGivney

How to Shit in the Woods: An environmentally sound approach to a lost art by Kathleen Meyer